Setting the Stage

My girlfriend and I were talking the other day about how weird it is that most American states seem to have capitals that are not their largest city. Upon further discussion, I thought of large cities like Salt Lake City, Utah (where I live), that actually are the state capital and the largest city. So we really wanted to know ‘are there more of the largest cities in each state that aren’t the capital versus those that are?’ But of course, a lot of questions abound when you think about this question: what do I mean by “largest city?” How would we answer this question given the operational definition of the largest city? Who cares?

Let’s start by getting our heads around the research question here. What I mean by “largest city” is the city that has the largest population. A cool thing about using this defintion is that the US Census estimates the population every 10 years. We could use other indicators of city size like area covered in squared miles, the city’s population density, or maybe an index score of population and area; however, we will go with population counts because it’s pretty easy to understand and say what the good, the bad, and the ugly is about using this operational definition.

Now we know how we are defining one central concern in this post. But what about answering the actual research question? This post is really about comparing the counts of how many of the largest cities in the United States are also the capital of that state. This is important: in answering this question, we will classify the largest city in each state as either the capital or not. One more thing: we won’t consider territories, commonwealths, or federal districts, like Puerto Rico or Guam. So, we will only be discussing the contiguous United States plus Hawai’i and Alaska.

Let’s talk data. I was really impressed with the Wikipedia page listing the United States and its territories by population. Its use of Census data and CIA World Factbook data leaves me confident of the accuracy of these population estimates. However, let’s be aware that these data come from Wikipedia, the Census from which these data come was conducted in 2010, and that the Census has unique ways for estimating the US population without surveying literally every household.

I converted the table in that Wikipedia article into tabular format and added a column denoting Yes/No if that largest city in that state is also the capital. Then I used the handy COUNTIF function in Excel to tally up the yeses and nos from that first tab of the sheet. You can find the data file (States.xls under /static/data) for this post in the associated Github repository. We are essentially left with a 1X2 table showing counts of how many of the largest cities in each state are also the capitals. Let’s read the data into R and look at them. Before we get to the good stuff, I’m using R version 3.6.3 (R Core Team 2020).

The Good Stuff

Let’s use the readxl (Wickham and Bryan 2019) package’s read_excel function to get the Excel data into R. I wanted to do a balloon plot visualization here to see the relative size of each cell, like this cool example, but the output is just too weird. This won’t stop us from looking at these data in other ways than raw counts.

states = read_excel(path, sheet = 2)

states## # A tibble: 1 x 2

## Yes No

## <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 17 33As we can see, it seems like most of the largest cities in each state are not the capital of that state. I want to visualize these data, but the tibble I imported isn’t playing nicely (I’m a newbie to R, so it’s definitely me). So, I created vectors below to get a bar plot to work.

count = c(17, 33)

largest = c("Yes", "No")

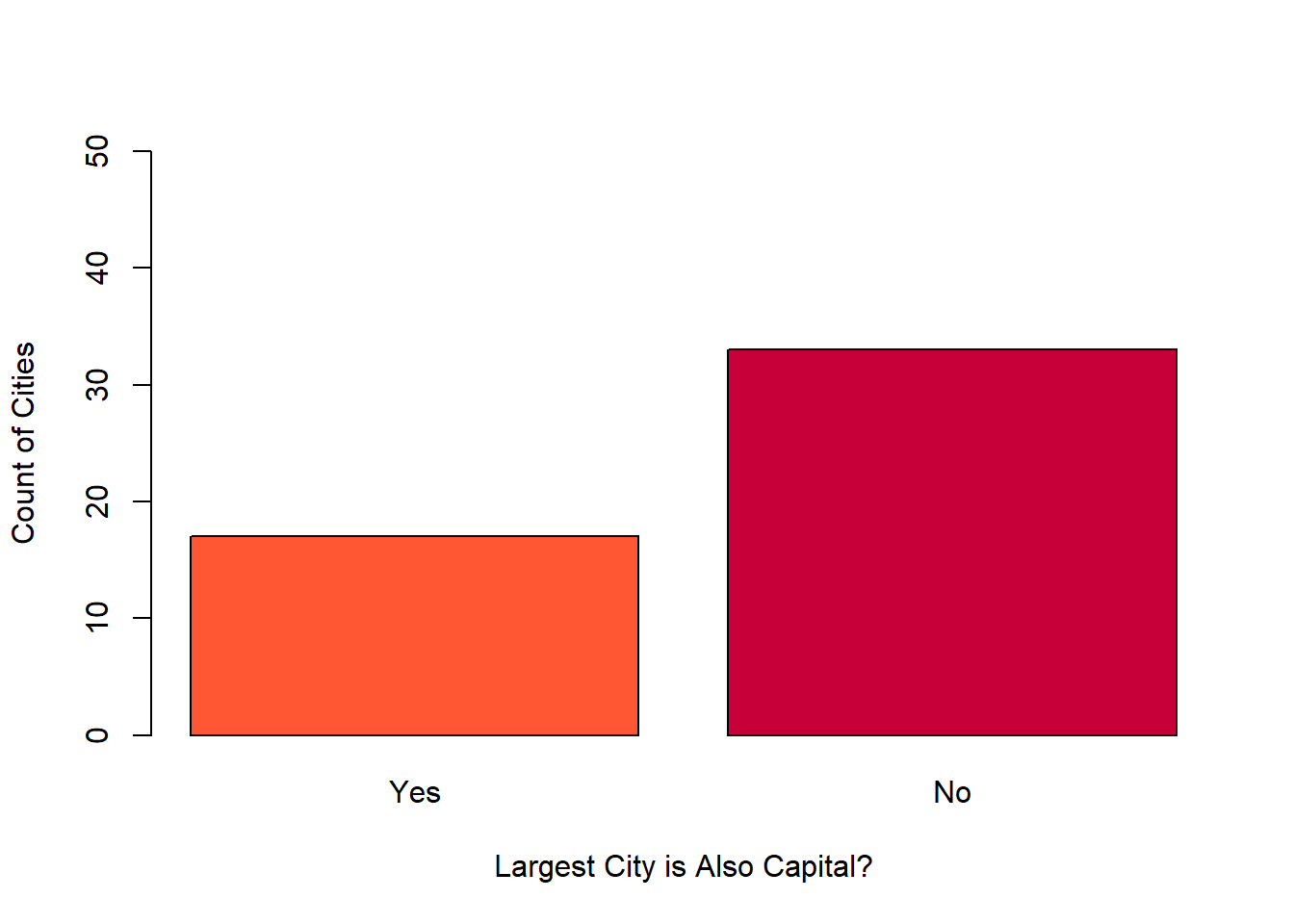

barplot(count, names.arg = largest, ylim = c(0, 50), xlab = "Largest City is Also Capital?", ylab = "Count of Cities", col = c("#FF5733", "#C70039"))

The bar plot of these data is cool because it lets us visualize that there is roughly double the proportion of largest cities that are not the state capital versus those that are. Let’s see these counts as proportions of the total.

states_prop = prop.table(states)

states_prop## Yes No

## 1 0.34 0.66Now we see just over 1/3 of the largest cities in each state is also the capital. But how would we see this with statistics using a null hypothesis test? Since the data we are using are counts, we are limited to nonparametric statistics. Why did I immediately say nonparametric? Because we are simply counting the variable we care about. Using parametric statistics implies using the ‘building blocks’ of general linear model statistics, meaning parameters of means and variances (Warner 2012). If we had meaningful parameters, we could use a correlation coefficient or another method; see Salkind and Shaw (2019) for a fantastic table breaking down the right correlation coefficient to use that compliments the classic and wonderful UCLA IDRE site on choosing the right statistical test for your needs.

Now let’s talk about which statistic to use and interpret. The chi-squared test is what we will be using and interpreting here, if you didn’t already notice the post tags. As usual, I think Salkind and Shaw (2019) do a fantastic job giving a plain-language summary of what the chi-squared goodness of fit and test of independence are, both mathematically and conceptually. We’ll be using the chi-squared goodness of fit test here given the data are unidimensional (i.e., there are not two dimensions, such as if we added whether or not the capital city was originally the largest in the state when it was established as the capital). Below is the formula for the chi-squared goodness of fit test and the null/alternative hypotheses. Using NHST (Warner 2012) with the chi-squared test, the null hypothesis is that there is no difference between the value we expect in each cell and the one we observe.

\[ \chi^{2}=\Sigma{\frac{{(O - E)}^{2}}{E}} \]

\[ H_0: O = E \] \[ H_1: O\neq E \]

The thing to notice above is the expected value. Applied here, the classic way of calculating the chi-squared goodness of fit test’s expected value is to take the total count we have (50) and divide it by the amount of cells (2). For our purposes, each cell having 1/2 of the total (25), seems pretty reasonable for expected values, given I don’t have other expected porportions that we might use instead. So, we expect 25 of the largest cities in each category, being the capital and not the capital. The observed values used are the counts that we looked at above. Below is the good stuff.

chisq = chisq.test(states)

chisq##

## Chi-squared test for given probabilities

##

## data: states

## X-squared = 5.12, df = 1, p-value = 0.02365observed = chisq$observed

expected = chisq$expected

observed## [1] 17 33expected## [1] 25 25\[ \chi^{2}(1)=5.12,{\,}p = .02 \]

The above are results of the chi-squared test, which I also pretty printed with MathJax below the code block. See those [1] rows? The first is our observed values, or the counts we discussed before. The second is the expected values. Notice how it defaulted to using the expected values how I defined them? Let’s come back to this in just a bit.

Okay, now we have results. But what about interpretation? That’s the real gig here. The chi-squared statistic is statistically significant at the .05 level. However, what does this really mean? It means that if the largest cities in each state were equally distributed across the capital/not capital categories randomly, we would observed 25 in each category. The actual observed values differ from these expected values and this difference is statistically significant; if the counts were equally distributed among categories, we would observe results this extreme or more extreme ~2% of the time. Thus, the observed amount of states with the largest cities also being the capitals does not fit the expected values (this is why it’s called the goodness of fit test).

Let’s come back to that expected value piece I pointed out earlier. Using the expected values of 25 of the largest cities each being and not being the state capital means that our interpreation above is sound. However, this definitely affects how we interpret our end results. I bring this up because the user can specify which probabilities they want R to use. Thus, I could’ve given R the vector p(1/1.25, 1/5) if I thought 80% of the largest cities would be the capitals and 20% not. Not to belabor the point, but this would change our interpretation. Instead of having statistically significant results departing from 25/25 in each category, we would have 40 of the largest cities in each state being the capitals and 10 not as the expected values. Having statistically signficant results versus this null hypothesis would mean that the observed values do not fit those counts.

So, where does this all leave us? We showed that the counts of American states’ largest cities being or not being that state’s capital are statistically significant that depart from having equally distributed counts. Thus, having 33 (66%) of states’ largest cities that are not the state capital and 17 (34%) that are departs from what we would expect by chance. As a reminder, these data come from the 2010 US Census. So, we couldn’t say that this has always been true or that it will hold true when the 2020 Census is completed. A more interesting question might involve adding a dimension of whether each state Capital was the largest city at the time it was designated as the capital. I didn’t structure the data this way because this would involve digging into historical population records, but not impossible given the first Census was conducted in 1790; so, this is possible fodder for a future post. These data also only involve population counts as the standard for determining the largest city and thus doesn’t involve anything like the city’s total area, as discussed above. As we think about the answer to this post’s question, we have to keep these limitations in mind. Thanks for reading, and send me any feedback you have!

References

R Core Team. 2020. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/.

Salkind, N. J, and L. A Shaw. 2019. Statistics for People Who (Think They) Hate Statistics Using R. Book. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Warner, R. M. 2012. Applied Statistics: From Bivariate Through Multivariate Techniques. Book. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Wickham, Hadley, and Jennifer Bryan. 2019. Readxl: Read Excel Files. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=readxl.