- Getting A Grip

- p-Values

- Step One: Assume The Null Hypothesis Is True

- Step Two: Convert Your Estimate to Standard Error Units

- Step Three: Determine The Probability of Observing Your Estimate

- Step Four: Apply Your Alpha

- Step Five: Compute The Probability of Your Sample Results

- Visual Example of p-Values

- Conclusions on p-Values

- Confidence Intervals

- Common Misconceptions

- Conclusions

- References

Getting A Grip

Aside from Theranos, I don’t know of any topic that has more mystique surrounding and people putting far too much stock (pun intended) into it than p-values. A very-much related, and probably less understood, topic is that of confidence intervals, which are essentially the stock market of the statistics world: no one understands them, but we all have a ton of speculation about what they’re doing. I mainly wanted to write this post after I saw a blog post in a very available data science blog talking about some really core topics in data science and statistics. Instead of going through the post’s assertions point-by-point, I’ll instead build a common sense interpretation of p-values and confidence intervals, which the reader can use to see for themselves if other sources of information on those topics get it right.

I’ll mainly use the family of tidyverse (Wickham et al. 2019) packages in this post (i.e., ggplot2 and dplyr). I strongly suggest using both if you use R frequently.

library(tidyverse)p-Values

How do we determine if there is a real relationship between things we study with data? I had a coworker read some article with a scientific claim and say ‘yeah, but how do they know that?’ I don’t remember what he was talking about, but it’s a fair question concerning about the use of statistics to study phenomena. What he was probably talking about was a gross summation of a study that used p-values as part of null hypothesis significance testing (NHST) to determine if there is a relationship between the topics in question.

Let’s break down the NHST process. I’ll use Baldwin (2019)’s process here, which is super useful to organize your thinking when interpreting statistics results. The steps in NHST are outlined below as headers. However, let’s first set a running example; we’ll talk about a hypothetical study where we measured weight, in pounds, as the outcome and reported hours of exercise per week as the predictor in a regression model. So, we would be left with a \(\beta\) coefficient denoting, with a one-unit change in hours per week of exercise, the predicted change of weight in pounds. Let’s say our fake study collected data on 1,000 people from the general population and used good sampling procedures.

Step One: Assume The Null Hypothesis Is True

I have a useful heuristic here: always think of the null hypothesis as zero. In actual terms, the null hypothesis in our example takes the form:

\[ H_0: \beta = 0 \]

The above essentially says that we start by assuming there is no relationship between weekly hours of exercise and weight in pounds in the population. It’s important to explore the zero in this sense. This zero is the center of the population that we are testing against. This is related to the aggregation of estimates in the long run. Let’s take a second for the population bit.

We say in the population between we take a sample from the population of interest, in this case the general population’s relationship between exercise and weight. If you sampled many times, doing the sampling in the exact same way, you’d get \(n\) number of \(\beta\) estimates. Your \(n\) estimates would theoretically form a normally distributed population of estimates centered around the one we observed in the sample (the \(\beta\) in your output). The point is that, when sampled to the infinitieth degree, you have a population of estimates with a center (\(\mu\)) that is your sample estimate and variance (\(\sigma^2\)) around that central estimate.

Okay, we have the null hypothesis, but what about the alternative (AKA research) hypothesis?

The alternative hypothesis is given by:

\[ H_1: \beta \neq 0 \]

It’s pretty easy to see that this is just the opposite of the null hypothesis.

The summation of the above is what leads to the language around accepting or rejecting the null hypothesis. So, you’re testing the null hypothesis, which is why we call its complement the alternative hypothesis. We’ll come back to this in step three and beyond.

Step Two: Convert Your Estimate to Standard Error Units

The standard error is the average deviation around the population’s central value (the estimate from your results); so, it’s how much each estimate would vary from the estimate we have, on average, when resampled many times. The standard error is also the units we use to put our estimate into so we can use the central limit theorem to make decisions. In more concrete terms, you take the observed \(\beta\), subtract zero, and divide the whole thing by the observed standard error to make it useful against a distribution, usually either the \(t\) or \(Z\) distributions. So, the equation is:

\[ t_{obt} = \frac{\beta_1 - 0}{SE_{\beta_1}} \]

So, your sample estimate is put into standard error units that deviate from a population centered on zero. This is incredibly important once we go through the next parts of the NHST process. In our example, let’s say we have \(t_{obt}=3.5\).

Step Three: Determine The Probability of Observing Your Estimate

This is essentially building your null distribution. Remember in step one where I tortured you by talking about the population of estimates and said it follows the normal distribution? We have \(E[X]\), which is the expected value in the population and equal to our \(\beta\) estimate from the sample we collected, as the center of that population. So, you’ve got the \(\beta\) from the sample as the center of the normal curve. The standard error (\(SE\), just like in the equation above) is the dispersion around that estimate.

Now I’m going to throw a wrench in the chain. The null distribution is the distribution we are talking about in this step. You’re taking the standard error you computed from the sample and using that as the standard error in your null distribution, where, instead of \(\beta\) you’ll use zero as its center. So, we are left with an estimate from step two, in standard error terms, that becomes less and less likely the more extreme in gets in units of deviance from the distribution with zero as its center. Essentially, the bigger the estimate gets, the less likely that it comes from a null distribution.

Step Four: Apply Your Alpha

By this I don’t mean this video shown in Silicon Valley. Baldwin (2019) has a fantastic section about this where he uses the words in this section’s header; we’ll explore his use of the word ‘applying’ the alpha in this context because its truly sage advice.

When we want to use NHST to make decisions, there is the null distribution, which we discussed above. Essentially, you’re saying that, in the long run, if you sampled a distribution where there is no relationship between two constructs – weight and exercise in our example – you’d get a lot of results centered on zero, indicating that there is no relationship between constructs in the long run. But what if the association between the constructs is so strong that it just isn’t true that there is no relationship? We need some standard to test against. Cue the \(\alpha\).

The \(\alpha\) you choose is essentially you picking a ‘risk level’ for making an incorrect decision. So what proportion, in a null distribution, would these results take place? If the results are extreme, when are you willing to say this isn’t due to chance and there is a relationship between weight and exercise? The essence is that we pick some percentage of time would take place in the null distribution and say that this is unlikely, indicating we should rethink embracing the null hypothesis. I mentioned making an incorrect decision because extreme results could always be sampled from a null distribution. There really could be no relationship between weight and exercise (I know this is a ridiculous example here), but we could obtain a sample from that null distribution indicating that there is. So, the alpha is a decision-making tool that could always result in an incorrect decision.

Picking an alpha is not an exact science. You’re essentially applying some arbitrary standard to say that, given a distribution of many different samples centered around zero, you would only observe results this extreme or more extreme some percentage of the time. Baldwin (2019) does a fantastic job covering this; essentially, he points out that, given an \(\alpha\) of .05, 5% of the null distribution is given as the arbitrary standard to say your results are not due to chance differences of your observed statistic from the null distribution. If you use an \(\alpha\) of .01, 1% would be your standard. This can get pretty confusing, so hold tight and we will run through these steps visually in just a second.

Step Five: Compute The Probability of Your Sample Results

In the NHST process, we now have an obtained \(t\) in our fake study; however, this doesn’t do us any good unless we can use it. That’s where this step comes in. Because we have so many observations in our fake study, the distribution we are comparing against is actually the \(Z\) distribution, and thus, we can use the built-in functions in R to compute the exact probability of observing a \(t\) of 3.5 or above.

2*(1 - pnorm(3.5))## [1] 0.0004652582The code above gives us \(p = .0005\), rounding to the fourth decimal place; this is an exact probability that you wouldn’t usually report (the convention, at least in psychology, is to just say \(p < .001\)). Breaking down the code, the code above works because the function pnorm() is telling us the probability of observing a \(Z\) below the quantile we use as an input; in less technical terms, when you know the \(Z\) value, you use it as an input and it tells you the cumulative probability at or below that value and thus you can use that to say the probability that is the opposite of that. So, the complement, given by subtracting this from one, is the probability of having a result this extreme or more extreme. We multiply this by two because of the type of test (i.e., one-tailed or two-tailed). Suffice to say, you will determine the probability of observing the absolute value of the observed statistic much of the time, and that’s why R and other similar programs often show you \(Pr(>\lvert(t)\rvert\), letting you know that the p-value shown is the probability of observing values greater than the absolute value of the observed \(t\) on both sides of the distribution.

The real magic from the above steps comes together in step five. The \(\alpha\) used most commonly is .05. Our results of \(p = .0005\) are more extreme than this; thus, we have results that are unlikely when applying an alpha level of .05, leading us to reject the null hypothesis and conclude that the \(\beta\) from our fake study is statistically significant. But, all of this seems confusing, so it’ll be easier to look at visually.

Visual Example of p-Values

The script below generates some standard normal data and plots it so we can demonstrate some key things. I’m really only doing this to show the graph below of the normal distribution.

x = rnorm(100000)

y = dnorm(x)

norm_data = data.frame(x, y)

norm_data %>% ggplot(aes(x = x, y = y)) +

geom_line() +

geom_vline(xintercept = 1.96, color = "red") +

geom_vline(xintercept = -1.96, color = "red") +

xlab("Standard Error") +

ylab("Density")

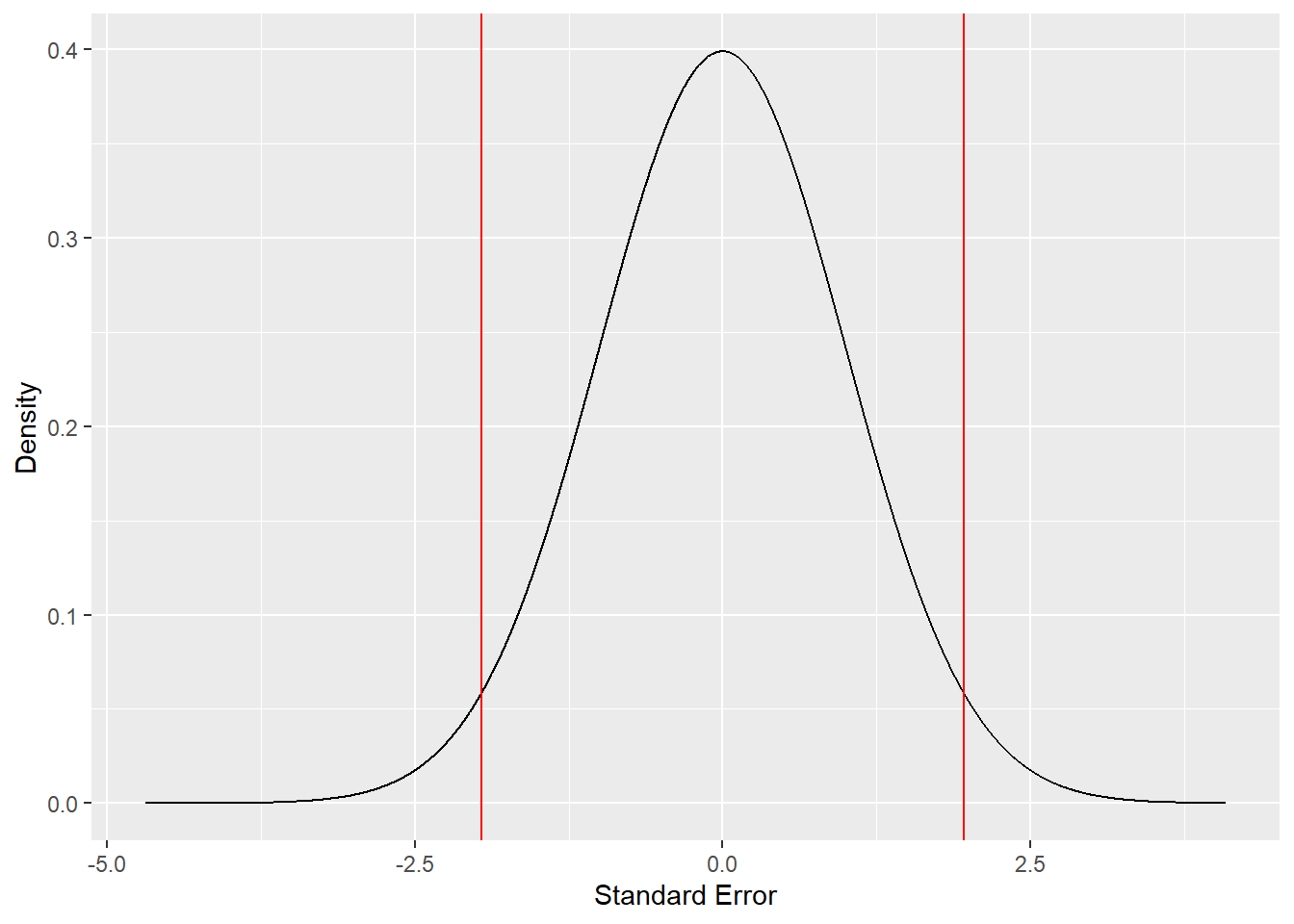

The graph above shows lines delineating 5% of the normal distribution contained in the tails. This is a visual showing us what an \(\alpha\) of .05 actually looks like. With a null distribution centered on zero and standard error units deviating from that center, which is what the x-axis shows, 5% of the distribution is more extreme than a \(Z\) of \(\pm 1.96\). Let’s now run through the NHST steps with our example much more quickly.

- Step One: Assume the null distribution is true.

- Step Two: Generate the obtained \(t\). We already said this was 3.5. Usually you would have data and run commands to get this, and the \(t\) would be calculated for you.

- Step Three: Build the null distribution. We have a null distribution in the graph above and an obtained \(t\), so we know where our results land in the distribution.

- Step Four: Apply your alpha. For this, we are really just seeing if our obtained \(t\) falls in the tails.

- Step Five: Compute a p-value. We have ours: \(p = .0005\). This complements our visual results and shows that the \(\beta\) in our fake study is statistically significant. We thus think it’s unlikely that this result comes from the null distribution and reject the null hypothesis.

Let’s look at this visually:

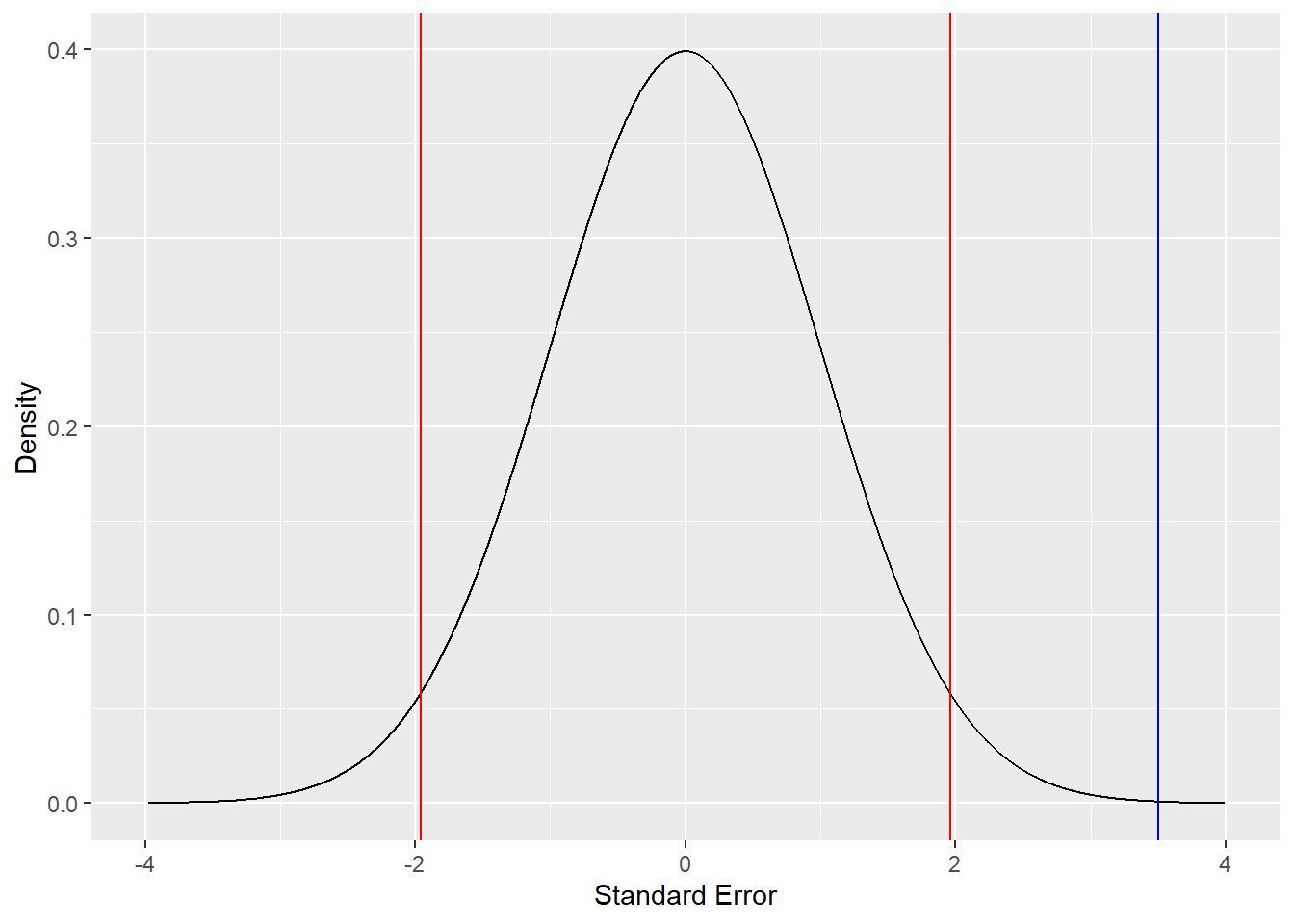

The blue line is our obtained \(t\) shown in the normal distribution. Clearly, our standardized value falls in the tails beyond \(\alpha = .05\).

The blue line is our obtained \(t\) shown in the normal distribution. Clearly, our standardized value falls in the tails beyond \(\alpha = .05\).

So, where does that leave us on p-values so far? I hope that showed us that it’s a structured approach to decision making. However, multiple points have to be emphasized here. The first is that there is specific language used to communicate the results; essentially, fill in the statement ‘given no relationship between [your constructs], results this extreme or more extreme would be observed [your p-value times 100] percent of the time.’ More concretely, in our study, we could say that, given no relationship between weight in pounds and hours of exercise, results this extreme or more extreme would be observed ~0.05% of the time. Thus, there appears to be a relationship between how many hours one exercises and their reported weight.

The second important point on p-values is that the alpha used is completely arbitrary. One professor once told me that \(\alpha = .05\) is “sacred.” This could not be more wrong. The alpha you use should always be a calculated decision as to the risk of Type I error; essentially, how often can you live with thinking that you’re right and actually being wrong? Is it 5% of the time? 1%? What about 100%, like in the article cited in the blog post I just linked? At the very least, report the alpha that you’re using to judge whether a result is significant or not.

The third and final point here is that p-values are not without controversy, even though they structure our decision making. Baldwin (2019) quoted Paul Meehl, reprinted here, on p-values a whopping 42 years ago:

“I suggest to you that [the creator of NHST] has befuddled us, mesmerized us, and led us down the primrose path. I believe that the almost universal reliance on merely refuting the null hypothesis as the standard method for corroborating substantive theories in the soft areas is a terrible mistake, is basically unsound, poor scientific strategy, and one of the worst things that ever happened in the history of psychology” (p. 64 in Baldwin’s text).

I’ll be honest, I think Paul Meehl was an asshole; his writing reads like the ultimate narcissist had enough intelligence to attend an Ivy League university. But, he isn’t wrong here. Using NHST is good for being lazy: you get to make a yes or no statement about a sample estimate, and this binary result of whether an estimate is significant or not is sometimes the only thing that gets reported in peer-reviewed journal articles, without actually interpreting the estimate itself. Scary, huh?

Conclusions on p-Values

From the discussion above, we can conclude that NHST and p-values are tools to be used with thought involved. The bedrock of what they’re telling you is whether your result from a sample, tested against a null population, is different from zero. A better way to do this is probably to have some idea of what the relationship between constructs is beforehand, and work to consider if the results obtained from your data differ from that; this general approach is called Bayesian statistics, and is way beyond the scope of this article. But, the idea does point out the problem with p-values and NHST. That is, is is reasonable to assume no relationship between the constructs you’re studying? To me, the guff that NHST gets is deserved, but it is useful from a utilitarian perspective. Using NHST, I can make statements about things like \(\beta\) estimates being statistically significant, which I can then supplement with things like predicted values, confidence intervals, and odds ratios. So, NHST is one useful tool that you keep in a tool belt to tell a story using data.

Confidence Intervals

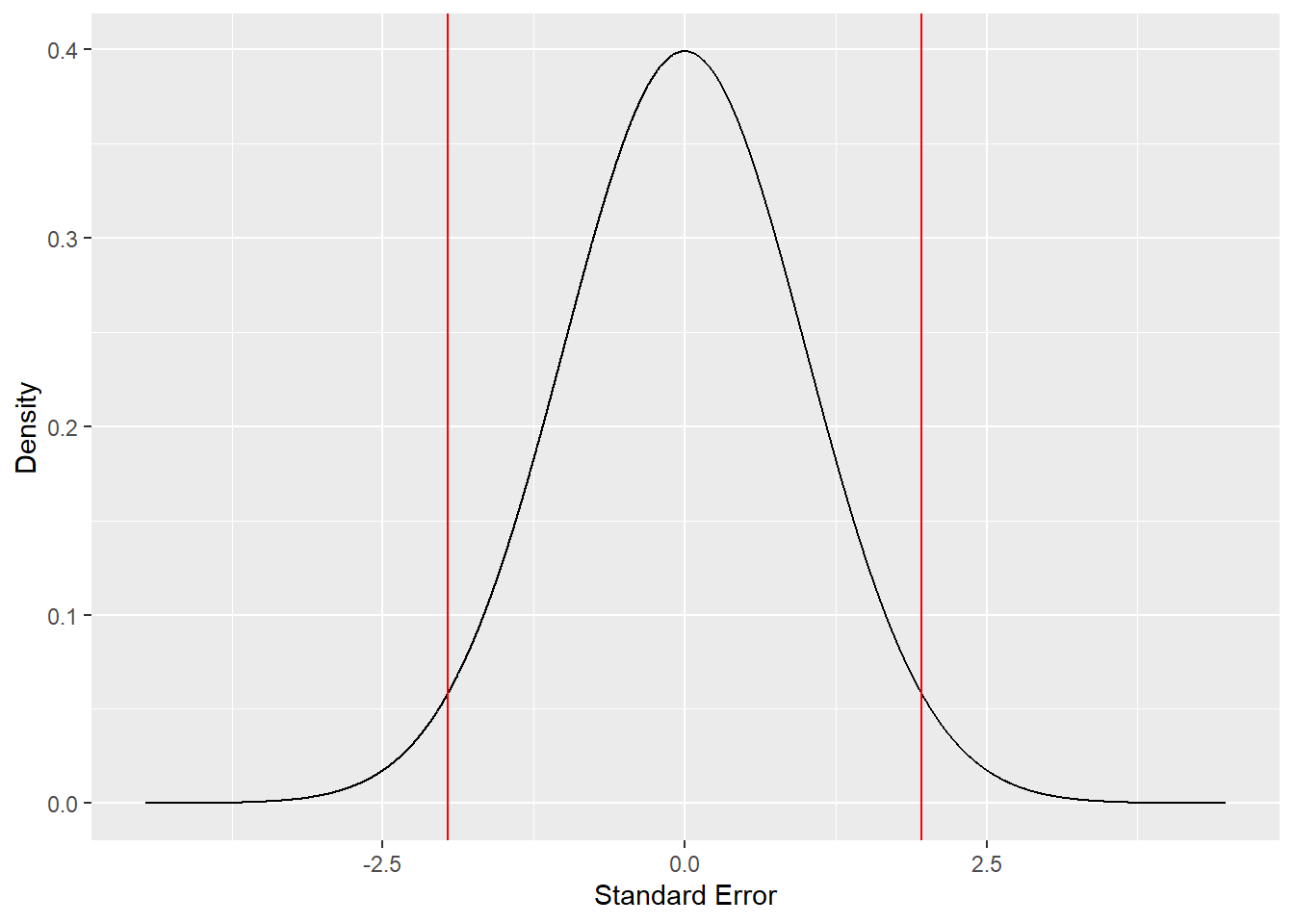

Before we delve into confidence intervals, let’s go over a piece of garbage you might see people talk about in relation to statistics: the ‘confidence level.’ I put the sarcastic paraphrase marks because this really isn’t a thing. It’s based on the idea that when you have a population distribution and select some \(\alpha\), that \(\alpha\)’s complement denotes your level of confidence. This is untrue. Let’s look back at the graphs above:

The idea is that the middle part of the distribution, bounded by the red lines, is the confidence level you have. Because the lines separate the inner 95% and outer 5%, you then have 95% confidence in your results. I ask you, dear reader, why would this be true? Nothing from the above discussion on NHST and p-values leads me to believe that the complement of \(\alpha\) is the percent confidence in the results. Instead, that percentage is just the percentage of the null distribution that is not represented by \(\alpha\). I mention this here because it has the unfortunate term “confidence,” which leads it to be misinterpreted, much like confidence intervals. Now we can talk about confidence intervals!

What Is A Confidence Interval?

The basic idea of a confidence interval (CI) is given below

\[ \beta-Z\cdot SE <\beta<\beta+Z\cdot SE \]

Where:

- \(\beta\) is your estimate obtained from your sample. This can be exchanged for any other estimate’s form (e.g., \(\hat{X}\))

- \(Z\) is the absolute value of the \(Z\) distribution separating the two-tailed region bounded by alpha, thus meaning that if you want a 95% confidence interval, use \(\pm 1.96\), just like the alpha of a two-tailed test where \(\alpha = .05\). Be careful here: this is usually just fine, but consider the distribution (e.g., \(t\)) you want to use and whether your hypothesis test is directional

- \(SE\) is the standard error of the estimate, which obviously changes based on what form your estimate takes

How Do I Use Confidence Intervals?

You’ll see confidence intervals out in the wilds of academia very often. Frequently, the estimate is accompanied by the interval around it in parentheses or brackets (e.g., ‘the \(\beta\) estimate of weight regressed on exercise is \(7.2, 95\%\ CI [3.17, 11.23]\)’). That’s great, but what do confidence intervals actually tell us?

The answer: not much. When you first learn about confidence intervals, you might hear something like ‘confidence intervals tell you, with some probability (e.g., 95%), the likelihood that that interval contains the true population parameter.’ This means that a lot of people think that there is some true population parameter, like 8.0 in the example interval above, and that the confidence interval covers the true population parameter by definition with some percentage of confidence, with 95% being common. Kind of like the confidence level, I really don’t know why this would be true.

Let’s look at CIs and what the actual interpretation is. Baldwin (2019) has a fantastic section in his book about this. The true interpretation of CIs is that, given an estimate, if you built confidence intervals around each and every number in the interval (i.e., \(7.2 \pm4.032\) in our example), up to \(\infty\) numbers within that interval, you’d get 95% of those confidence intervals containing your original estimate. I really urge you to check out Baldwin’s tutorial here to get a full meaning of this; it’s better to see it visually, and Baldwin does it gracefully, kind of like how seeing a simulation of the Birthday Problem helped Paul Erdos see that it was correct. Suffice to say, Baldwin’s words (p. 61), in the block quote below, ring true:

Given this awkward interpretation of confidence intervals, I recommend you focus more on the width of the confidence interval rather than the specific numbers. In other words, use the confidence interval to learn about uncertainty rather than making probability statements about the population value.

I do have something to add here, though. If you’ve taken a statistics class and CIs have been mentioned, you might have heard ‘if the interval contains zero, that means your result isn’t significant’. I’ve never found that intuitive, so it’s useful to break down the math here and show why that’s true while digesting the math in Zen’s answer on that post. Let’s look at how to tranform the equation above:

\[ \beta-Z\cdot SE <\beta<\beta+Z\cdot SE \]

Dividing the standard error term from every part of the inequality gives us the standardized estimate in the middle, just like step two of the NHST process, and bounds that make understanding the relationship with statistical significance much easier:

\[ \frac{\beta}{SE}-\frac{Z\cdot SE}{SE} <\frac{\beta}{SE}<\frac{\beta}{SE}+\frac{Z\cdot SE}{SE} \] Which simplifies to:

\[ t-1.96 <t<t+1.96 \]

Here’s the thing to understand and link to the NHST process: if you estimate (\(t\)) is greater than the \(Z_{crit}\)/\(t_{crit}\) for your chosen alpha, it is, by definition, more than that many standard error units away from zero. Therefore, from the equation above, if that lower or upper bound crosses zero, it means your estimate is not far enough away from a population centered on zero to be statistically significant. Let’s look at this visually:

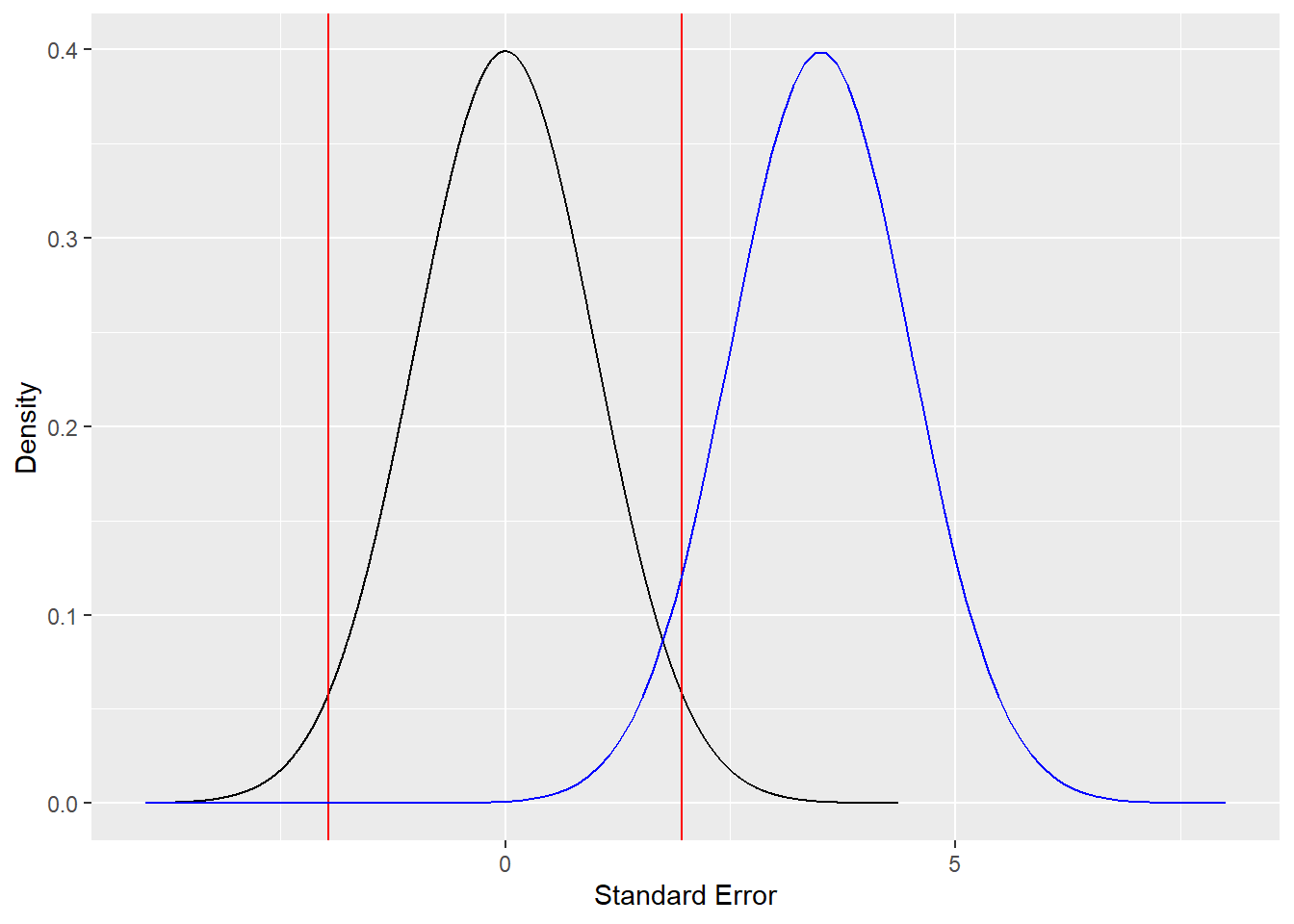

Now we have two distributions on the same graph: one centered on 0, and one centered on 3.5, in standard error units. The red line still shows the \(t_{crit}\) for rejecting the null hypothesis. We see that the observed population of estimates, centered on 3.5, is clearly beyond the critical threshold, and is 3.5 standard error units away from zero; to beat a dead horse, this is greater than the needed 1.96 standard error units needed to reject the null hypothesis. This is essentially just the discussion above warmed over; however, to bring it back home, consider our fake interval of \(7.2, 95\%\ CI [3.17, 11.23]\). The interval doesn’t contain zero because the estimate is more than 1.96 standard error units away from zero. Consider any other distribution, degrees of freedom, and one-or-two-tailed nature of the test, this still still hold true: if the interval contains zero, it isn’t significant per your defined alpha, which changes the \(Z\) or \(t\) term used to calculate the interval. Now that we have a common understanding, let’s address some more common misconceptions.

Now we have two distributions on the same graph: one centered on 0, and one centered on 3.5, in standard error units. The red line still shows the \(t_{crit}\) for rejecting the null hypothesis. We see that the observed population of estimates, centered on 3.5, is clearly beyond the critical threshold, and is 3.5 standard error units away from zero; to beat a dead horse, this is greater than the needed 1.96 standard error units needed to reject the null hypothesis. This is essentially just the discussion above warmed over; however, to bring it back home, consider our fake interval of \(7.2, 95\%\ CI [3.17, 11.23]\). The interval doesn’t contain zero because the estimate is more than 1.96 standard error units away from zero. Consider any other distribution, degrees of freedom, and one-or-two-tailed nature of the test, this still still hold true: if the interval contains zero, it isn’t significant per your defined alpha, which changes the \(Z\) or \(t\) term used to calculate the interval. Now that we have a common understanding, let’s address some more common misconceptions.

Common Misconceptions

- p-values indicate levels of significance, and it makes sense to talk about how extreme the p-value is.

For instance, you might see something like ‘these results are highly significant.’ Nope. It’s a binary decision, so this language never makes sense. Your estimate is either statistically significant or not in the NHST process.

- You can talk about results with levels or percentages or confidence.

No. For confidence intervals, this is just an unfortunate side-effect of the word “confidence” being in their name; I’m not sure who could have possibly thought that \(1-\alpha\) denotes a level of confidence. To be safe, steer clear of this language when communicating results.

- There is a ‘default’ p-value, and there are other default values.

I mean, kind of? Depending on the statistical software you use, it might tell you whether your observed statistic is significant at the \(\alpha = .05\) level as a default. R is really cool in that it will denote, with those classic stars, whether results are significant at different levels, at least on certain tests (e.g., linear regression). I really caution you though, think about what \(\alpha\) you’re using and why. If you have an alpha in mind and know your degrees of freedom, you can use the standard error term from your output and think through whether your standardized estimate is significant.

Conclusions

I’ve put some conclusions above, so I’ll keep this section light. We can conclude that misconceptions about p-values are common, and that, even with well-meaning explorations of these topics, it’s easy to get them wrong. Don’t fret if you find it tough, but think through what NHST processes are actually telling you, what you’re assuming or doing by default, and force yourself to write down your interpretations of what a statistical analysis is telling you. Thanks for reading, and send me any feedback you have!